When journalist Nathan McCall released his 1994 autobiography, Makes Me Wanna Holler: A Young Black Man in America, my mother was among the first wave of people to purchase a copy.

She didn’t buy the book for me as a young aspiring journalist who was still in college at the time, although I’m sure she would have. Rather, my mother bought McCall’s book for herself because – like many readers – she was riveted by a report on NPR about McCall’s remarkable foray into the newspaper business after having served time in prison for robbing a McDonald’s. She was particularly taken aback by the fact that McCall had gotten tougher treatment for the armed robbery than when he tried to shoot a Black person – an indication, McCall wrote, of how little regard the system had for “the value of Black life.”

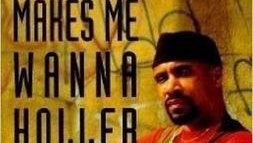

Makes Me Wanna Holler: A Young Black Man in America, by Nathan McCall

Makes Me Wanna Holler: A Young Black Man in America, by Nathan McCall

For me, the most memorable passages were not about McCall’s street endeavors or his time in prison, but rather his claim about how Black journalists often find ourselves “on guard” because of constant skepticism about our skills. Every Black journalist, McCall wrote, has heard these whispers of inferiority “a million times” in their careers.

“Success in journalism is tied directly to a writer’s psychological state. You need to be relaxed to write well,” McCall wrote. “Because of the myths, I could never seem to settle down and relax and write with flair the way I knew I could under normal circumstances.”

When I first read those words, I thought maybe McCall was making excuses. He survived prison but couldn’t hack it in a newsroom? Besides, even “normal circumstances” at a newspaper are often stressful – not relaxed – especially for a reporter who is on deadline for a breaking news story.